Comprehensive Assessment of Social Communication

This article will go over:

- The assessment areas of social-emotional, interoceptive awareness, and self-advocacy

- A discussion of:

- Assessment of non-instrumental, higher order pragmatics skills

- Nonverbal language decoding

- Nonverbal signals

- The impact of social communication skills on academic success and social interactions

- The factors that impact pragmatic performance

- Video Based Assessment techniques

- The differentiation between strengths-based and diagnostic evaluations

Over the years, there have been many advances in the field of speech and language, none as significant and revolutionary as the use of videos in the area of both assessment and intervention. The storytelling power of videos, with real life people, and real life scenes, are being used today to assess students and to teach social communication. This blog will go through specific examples of how to use dynamic videos of real-life scenes to accurately assess students’ pragmatic skills. We will also discuss the six areas of pragmatics that can help SLPs obtain comprehensive and more accurate results. We will review and analyze the impact of self-awareness and interoception on social communication and how assessment of higher order pragmatic skills can be achieved in an efficient and authentic way using real-life videos. We will also review nonverbal language, how it can affect social interactions, and how it can be assessed more accurately using videos. We will discuss the factors that impact pragmatic performance and also, how pragmatic language can impact academic success. We will take a look at strength based assessments versus diagnostic assessments.

Before we begin to discuss assessment strategies, we need to have a clear understanding of what it is that we are assessing… what exactly does the area of pragmatics entail?

Let’s take a look at the traditional definition of pragmatics, these are some examples of definitions we were taught in graduate school.

“Knowing when to say what to whom and how much” or communicative functions (reasons for talking), the frequency of communication, and discourse skills (turn-taking, topic maintenance and change, requests for clarification). This is technical information that only takes into account the superficial layers of social communication. It is not helpful! Unfortunately, this view of social communication often leads researchers and clinicians to assessment approaches that only assess the superficial layers of pragmatics instead of the deeper levels.

Social communication is much more than knowing how to initiate or maintain a conversation, or eye-contact or body language. It entails so many more important components like the ability to connect with others, understand emotions and to empathize, recognize intent, express emotions, and make/maintain friendships.

It is rare that we see any analysis on the impact on social and academic life.

We like to view pragmatics as the final ingredient needed for effective communication.

Pragmatics entails connecting and socializing with others, which is emotionally driven. Why do we socialize on a daily basis? We socialize to feel connected, supported, validated, understood, to share our feelings/thoughts about news, events, decisions, and to feel secure at our workplace, at school, etc. But in order to achieve this successfully, we need a solid understanding of our own emotions and others’ emotions.

At the very core of social communication lays emotion and intent. Our emotions and intent are surrounded with paralinguistics, social behavior, and verbal communication.

A child’s ability to understand their own emotions and identity is the foundational piece in understanding and connecting with others. Successful communicators are able to identify their own feelings and the feelings of those around them.

Communicating with others is like driving a car on a busy road. When you are driving, you understand how your car works, how it was built to run, you understand the rules of the road and how to get along with other drivers on the road. In life, we also need to know how to understand and get along with others, how to connect, and follow the “social rules” of life. Just like understanding your own car, others’ cars, and other drivers, leads to success on the road, understanding your own emotions and others’ emotions leads to success in life.

So at the core of social communication we have:

- self-awareness: understanding meanings of our own emotions and needs

- self-regulation: managing our own emotions

Emotions are our reactions to our current situation, environment, happenings, events or our memories. Our emotions can be based off a response to a current event or similar event in the past. The way we handle emotions is based on our ability to tolerate the emotion. Emotions vary in intensity. They can be strong, they can be intolerable, they can be weak.

Emotions and our ability to tolerate the intensity of our emotions drive our social behavior and communicative intent.

Examples of how Emotion Drives Social Communication

- Being alone —–> Reaction: feeling lonely ——> Intent to socialize to feel better

- Watching an impactful news report ——> Reaction: forming an opinion, feeling excited ——> Intent to share/discuss opinion with others

- Receiving sad news from a friend ——> Reaction: understanding what it feels like to be in friend’s situation ——> Intent to empathize to help friend feel better (to maintain friendship)

As students get older, and with greater maturity level, the complexity of emotions and intent increases. For example, the emotion of feeling accepted/rejected, annoyance, disgust, loneliness, become more apparent and complex.

Teenagers begin to understand and view social ranks at school (e.g., popular vs. unpopular social groups on campus), social status, special interests (video games, fashion, sports), sarcasm, and deceit, etc.

So, teenagers who are emotionally less mature than their peers, or students with comprehension difficulties often show significant difficulties in understanding complex types of intent like deceit, sarcasm, and popularity.

What happens when there is a difficulty in processing or understanding meanings of emotions or detecting intent? All the surrounding areas of social communication will be affected.

Interoception is one of our senses that helps us understand and regulate emotions and allows us to answer the question, “How do I feel?” Interoception helps us process our own emotions and understand how we feel. Interoception has a large role in an individual’s ability to engage in perspective taking and understand how others are feeling.

Before we are able to demonstrate interoception, we need to be able to discriminate and understand our own emotions. Once we have developed interoception, we can begin engaging in perspective taking and stepping into someone else’s shoes. We are not only answering the question, “How do I feel?” but also, “How do you feel?”

So now we are starting to put the pieces together and see a clearer picture of pragmatics and how it works. Emotions are our constant and continuous reactions and interoceptive awareness and self-regulation (or management of our own emotions) create communicative intent, which is the basis for any socialization. Surrounding pragmatic language areas, such as perspective taking and nonverbal language are influenced by our emotion and expression of intent.

A child with social communication differences may have difficulty with:

- Taking turns during conversation;

- Maintaining a conversational topic;

- Introducing new/appropriate topics;

- Understanding presuppositions;

- Comprehending nonliteral language; and

- Interpreting verbal and nonverbal cues.

This is what we may see on the surface, but what are the underlying reasons for the social communication differences? Is it self-regulation? Interoceptive awareness? Limited experience learning about/engaging in conversations with peers?

Traditional view: Students who have difficulties understanding others’ perspectives or understanding that other people have their own thoughts, ideas, and motivations likely have difficulty understanding their own emotions or overflow of emotions. These students may have weak interoceptive awareness which leads to difficulties understanding emotions of others.

*Note: This does not mean that autistic children don’t understand that people have their own thoughts, ideas, and motivations.

Turn-Taking: Students may have difficulty taking turns during conversation. Students may interrupt conversations, or cut someone’s thought process off. This is likely due to weaker self-regulation and the need to share information at the exact moment. The emotion of wanting to share information can be heightened making it difficult to tolerate and wait for one’s turn.

Maintaining a conversational topic: Introducing new/appropriate topics is most affected by weaker interoceptive awareness and also limited or reduced experiences having true conversations with peers, understanding nonliteral language ( e.g., non-literal language is usually used to emphasize an emotion or a concept, for example, “Man! It’s raining cats and dogs!” Here, you are emphasizing your frustration, or it’s a way to express/emphasize an emotion. This may be difficult to read for those students who experience and process emotions differently).

Detecting nonverbal cues: Students may have difficulties/differences detecting nonverbal cues because they have difficulty processing their own emotions compared to typically developing kids)

It may be helpful to look at the difficulties/differences in social communication in light of the underlying cause because we may see a completely different picture and take a different assessment and intervention approach.

Diagnostic versus strength-based evaluation

There is often conflicting information in the field of speech-language pathology regarding the use of standardized assessments in the area of pragmatics. Some researchers argue that standardized assessments should not be used and only strength-based assessments should be used, however, it is important to remember that strength-based assessments are used for a different purpose than establishing whether a disorder is present or not. It is helpful to use both types of assessments as standardized tests help us to identify a disorder and strength based assessments help us better understand the disorder once it has been identified.

The purpose of a diagnostic evaluation is to:

- compare student performance to a group of neurotypical students in the same age-group;

- evaluate how the student functions in a neurotypical academic and social setting;

- determine eligibility;

- develop a profile of strengths and weaknesses; and

- determine or rule out a diagnosis.

The purpose of a strength-based evaluation is to:

- promote an enabling environment;

- focus on changing the environment, NOT the student;

- focus on self-esteem, autistic identity and autonomy;

- move the burden of change away from the student and foster acceptance and accommodation so that the student can integrate/participate as much as they wish; and

- focus on self-advocacy, self-awareness, problem-solving.

Limitations of common standardized assessments:

- Non-existent or poor sensitivity/specificity properties

- Reliance on static images that present exaggerated facial expressions

- Outdated images

- Requires an SLP to read out loud a social situation which may not properly convey the message of the presented social scene

- Assesses basic instrumental pragmatics such as problem solving skills instead of social interactions. For example, “What will happen if you break something in the supermarket ?” or “Why do you have to look both ways when crossing the street?” These items relate more to activities of daily living instead of social interactions.

- Does not address the complex dynamics of nonverbal language

- Does not accurately detect social communication difficulties

The CAPs is the first and the only pragmatic language assessment that uses real-life videos of social interactions and evaluates nonverbal language as well as presents with excellent sensitivity psychometric properties.

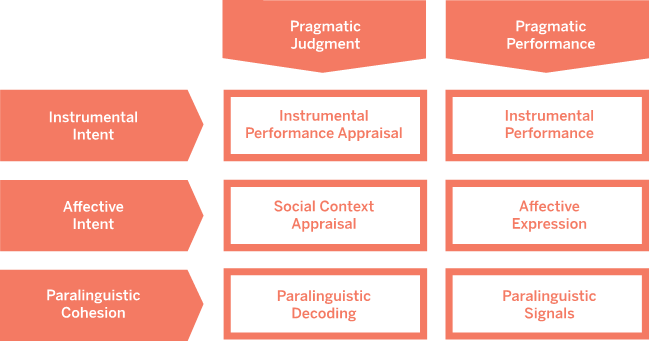

Pragmatic Judgement versus Pragmatic Performance

When we separate pragmatics into two domains, pragmatic judgment and pragmatic performance, we can better understand the receptive and expressive components of pragmatics. We can better understand how much awareness our students exhibit in social situations, and also how well our students are able to use their awareness, apply it, and express themselves socially.

Traditionally, pragmatic judgment has been referred to as the ability to appropriately understand and use language. However, it’s important that we distinguish between receptive pragmatics (judgment) and expressive pragmatics (performance) when we are assessing social communication so that we can separate and understand our student’s awareness and comprehension of social context and responses and reactions to social situations.

Assessment of both areas of pragmatics can have have significant implications to therapy. For example, if a student demonstrates stronger judgment skills, targeting comprehension, and understanding of social context would be a waste of valuable intervention time. Instead, it would be highly beneficial to jump straight into applying the student’s knowledge to practice and role playing.

Intent

It’s important to analyze pragmatics in terms of intent. Specifically, instrumental intent, affective intent, and paralinguistic cohesion.

Instrumental intent

Instrumental intent has to do with basic everyday routine language that is needed to satisfy basic needs. So, there is little emphasis on emotion. When designing a treatment plan, it’s important to think about what type of situations we want to target or what kind of communicative intent that our students can read and express.

Affective intent

Affective intent is used to express emotions to another person and requires higher level thought processing. Affective communication is a key component of nonverbal communication.

Paralinguistic Cohesion

Paralinguistic cohesion includes both comprehension of nonverbal language, as well as the use of nonverbal language such as facial expressions and inflections. Paralinguistic cohesion is the ability to integrate recognition of nonverbal language and expression of various types of intent with help of nonverbal signals, like facial expressions, tone of voice, inflections, gestures, prosody, and overall body language. Currently, there are very limited resources that target nonverbal language (i.e., decoding facial expressions, using facial expressions and inflections), yet this is one of the most common areas of need.

Can you think of a time where something you said was misinterpreted due to your body language, facial expression, or tone of voice? Perhaps it was just a simple miscommunication but suddenly you find yourself in an argument with a friend, or significant other. Think about how often you use nonverbal language to communicate. Through our research, we have found that that the area of paralinguistics is where the vast majority of our students with social communication difficulties showed the greatest need.

Paralinguistics is one of the most predictive areas that help us identify true social communication deficits because when we are able to appropriately read nonverbal language, we are able to provide appropriate verbal responses. Thus, reading nonverbal language is crucial for social communication because it helps us understand what a person is feeling and thinking without the use of words.

Remember: Nonverbal language is not just about facial expressions, body language, and gestures. Its also about inflections, prosody, and intonation.

Unmasking the face – What do the universal expressions of emotion look like?

Paul Ekman and Walter V. Friesen’s (2003) “Unmasking the face: A guide to recognizing emotions from facial clues” examines what the universal expressions of emotions look like.

The authors focused on the three areas of the face which are capable of independent movement – (a) the brow/forehead; (b) the eyes/lids and the root of the nose; and (c) the lower face, including the cheeks, mouth, most of the nose, and the chin. Ekman and Friesen (2003) found that common emotions are conveyed in the upper part of the face, which is interesting to think about since we know that children with autism primarily focus on the lower part of the face.

Suggested assessment domains:

Basic Social Routines – these skills are necessary to navigate neurotypical social routines

Potential Treatment goals:

- Student will describe their perception of events and social situations

- Student will describe how their communication choices and actions may be perceived by those around them

- Student will self-determine their communication choices

- Student will identify specific environmental modifications they may need

- Student will identify sensory supports needed for self-regulation (e.g., What can be done to help calm their body if feeling overwhelmed or what can be done to help wake their body when feeling tired/bored)

Reading context cues – involves perspective taking and processing interactions between: contextual variables such as physical setting and environment, communication partners, communicative intent, conflict/solution, etc.

Potential Treatment goals:

- Student will describe the possible motivations and perceptions of others;

- Student will self-advocate for clarification when they do not understand what’s happening in the conversation;

- Student will self-advocate to navigate a conversational break-down;

- Poorly worded goal: Student will engage in a reciprocal social play by maintaining at least 3 social exchanges.

- More appropriately written goal: Student will self-advocate for a different activity, clarification of the game rules, or a break.

Using Social Routine Language

Potential Treatment goals:

- Student will describe supports and accommodations they need to self-regulate

- Student will communicate environmental needs for self-regulation and successful learning to their teacher/ school staff (e.g., I need a quiet place to get my work done)

- Student will self-advocate for personal needs (e.g., ask for help, to use the restroom, get some water, etc.)

- Student will self-advocate for sensory supports by seeking out one of the established IEP accommodations

- Poorly worded goal: Student will accept changes in schedule/ routine by demonstrating appropriate behaviors given verbal/visual cues

- More appropriately written goal: Student will identify and use coping skills and available resources in response to a change in their routine/schedule.