Determining Eligibility and “Adverse-Effects” on Educational Performance

The Individual’s with Disabilities Act (IDEA, 2004) emphasizes that when determining eligibility and related services for a student, the Individualized Education Program (IEP) team members must determine whether or not an impairment will negatively impact the child’s educational performance. The following article will discuss:

- Impact-related components of a legally defensible and evidence-based assessment;

- Determining adverse educational and social impact;

When we attend an IEP meeting for any one of our students, we discuss whether the student’s difficulties, or disability, will impact their educational process. During this discussion, and creation of the official IEP document, the IEP team is typically required to “check a box” or make a statement that indicates whether or not the team believes the child’s disability will in fact impact their educational progress. Often, we use “cookie cutter” phrases that state there is a significant impact, but these statements do not provide enough information. As such, parents, colleagues, advocates, or attorneys may question how the IEP team determined eligibility and educational impact. How was the decision made that the child’s disorder may likely impact educational progress? This is where evidence based formal and informal assessments and tools come in to play.

Speech/Language Eligibility Determination

By using the appropriate methods, speech-language pathologists use the following principles set out by IDEA in determining eligibility criteria that:

[1] the student has an impairment; and

Through the use of formal and informal assessment tools, SLPs address the first principle set out by IDEA in a straightforward manner by answering the question, “Does the student have an impairment?”

SLP conducts assessment to determine if: [1] the student has an impairment;

(34 CFR S300.8)

[2] the impairment results in an education impact, requires specially designed instruction

Through the use of observations, reviewing educational records, collecting evidence of academic performance (including documents from class assignments, independent and group work, class tests, etc), SLP analyzes classwork compared to the performance of grade level peers on the same measure

SLP determines whether [2] the impairment results in an education impact, requires specially designed instruction

(34 CFR S300.8)

IDEA Definition for SLI: 34 C.F.R. §300.7 Child with a disability. (c) Definitions of disability terms. (11) Speech or language impairment means a communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice impairment, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

Through the use of formal and informal assessment tools, SLPs can address the first principle set out by IDEA in a straightforward manner by answering the question, “Does the student have an impairment?” The second principle is a bit more complex because we are tasked with answering more than just one question. Firstly, if an impairment is found, we must consider whether special education services are needed. For example, a student may have an impairment but the impairment may not result in an educational impact and in which case, specially designed instruction would not be warranted. On the other hand, when impairments do impact a student’s ability to access to the curriculum, we must consider the nature of the impairment and how the disorder may interact with curricular demands in ways that impede access to general education. When making this determination, IDEA states we must do the following in order to connect performance and curricular functioning:

- IDEA does not allow the use of any one measure or assessment as the sole criterion in determining if a child has a disability or in determining an appropriate education program (U.S. Department of Education, 2006. CFR 300.304 b. 2).

- IEP teams must use a variety of both formal and informal assessment tools (U. S. Department of Education, 2006; 34 CFR §300.304 b).

- School-based SLPs can conduct classroom observations, checklists, play-based assessments, language samples, standardized and norm reference tests, narrative assessments, and speech intelligibility measures.

- IDEA (2004) states that when assessing a student for a speech or language impairment, we need to determine whether or not the impairment will adversely affect the child’s educational performance.

What exactly are adverse effects? Neither federal nor state law defines what “adversely affect educational performance” means. So, a review of the court cases interpreting this phrase may be useful to better understand. A court case involving Yankton School District determined that education is adversely affected if, without certain services, the child’s condition would prevent them from performing academic and nonacademic tasks and/or from being educated with non-disabled peers [Yankton School District v. Schramm, 93 F.3d 1369 (8th Cir. 1996).]. In California, the administrative hearing office has found poor grades and falling behind academically to be a primary indicator of an adverse effect on educational performance. [Lodi Unified Sch. Dist., SN 371-00; Capistrano Unified Sch. Dist., SN 686-99, 33 IDELR 51; Ventura Unified Sch. Dist., SN 1943-99A; Murrieta Valley Unified Sch. Dist., SN 180-95, 23 IDELR 997.]. Thus, when we consider “adverse effects” it is important to consult with teachers, parents, and other service providers to get a full picture of how our student is performing academically and whether they are having difficulty due to their disorder.

Now, let’s look into the determination of disorder component in more depth.

Federal law (20 USC §1414(b)) requires school districts to do the following:

- Use a variety of assessment tools and strategies to obtain relevant, functional and developmental information and academic instruction;

- Include information provided by the parent that may assist in determining whether the child is a child with a disability and the content of the child’s IEP;

- Include information related to enabling the child to be involved in and progress in the general curriculum, or, for preschool children, to participate in appropriate activities;

- Not use any single procedure as the sole criterion for determining whether a child is a child with a disability or determining an appropriate educational program for the child, and to use technically sound instruments that may assess the relative contribution of cognitive and behavioral factors, in addition to physical or developmental factors.

A common misconception is that “2 standardized tests must be used for eligibility purposes,” however, IDEA does not say anything about the requirement of 2 standardized tests for eligibility purposes. IDEA states do not use only one single measure! I repeat, IDEA does not say anything about using multiple tests or using 2 of the same types of tools/strategies. IDEA guidelines state a variety of tools and strategies must be used.

Additionally, IDEA does not say anything about severity as it relates to eligibility and does not require determination of severity level.

This is what the law actually states:

- (b)(2)(A) use a variety of assessment tools and strategies….

- (b)(2)(B) do not use a single measure or assessment as a single criterion…

- (b)(2)(C) use technically sound instruments that may assess…

- (b)(3)(A)(i) …not to be discriminatory…

- (b)(3)(A)(ii) .. in the language and form most likely to yield accurate information…

- (b)(3)(A)(iii) … are valid and reliable;

- (b)(3)(A)(v) are administered in accordance with any instruction by producer…

- (b)(3)(D)assessment tools and strategies that provide relevant information that directly assists persons in determining the educational needs…(20 U.S.C. §1414(b))

It also requires the use of additional procedures:

- A) review existing evaluation data on the child, including—

- (ii) current classroom-based, local, or State assessments, and classroom-based observations; and

- (iii) observations by teachers and related services providers (20 U.S.C. §1414(c)(1))

By using both formal and informal assessments, clinicians are able to capture a better picture of a student’s speech and language abilities and whether there may be adverse effects on educational performance.

So our next question should be, how can we analyze the impact of a speech and language disorder in an objective and fair way?

-

Language/Speech Samples

-

Narrative Analysis

-

Report Cards/ Work Samples

-

State Testing

-

Parent/Teacher Input

-

Curriculum based measures

-

Observations

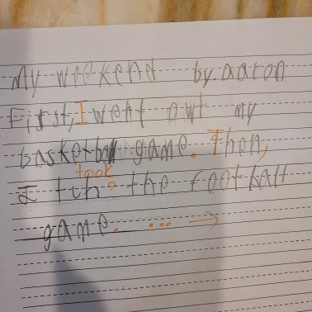

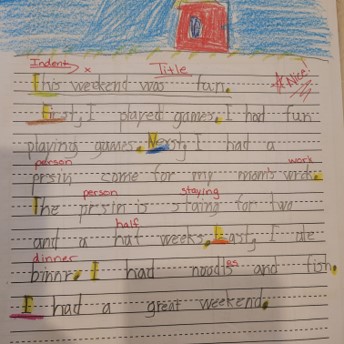

Analysis of school performance includes reviewing educational records, collecting evidence of academic performance (including documents from class assignments, independent and group work, homework, class tests, and portfolios of class performance), and completing observations across a variety of educational contexts (classes, playground, extra-curricular activities, lunch, etc.). These observations provide insight into the student’s speech language performance during real communication tasks. (Virginia Department of Education, 2011)

Classwork that demonstrates limited ability when compared to the performance of grade level peers on the same measure.

Selecting Assessment Tools with Strong Psychometric Properties

When selecting an assessment for a speech and language evaluation, it is important to consider whether it is truly a good assessment tool. A good assessment is one that produces results that will benefit the individual being tested or society as a whole (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education [AERA, APA, and NCME], 2014). There are a few ways we can examine whether a test is considered a good and strong assessment. We can take a look at the standardization, normative information, and the psychometric properties of each test.

Introducing: The IMPACT Model (Lavi, 2020)

The IMPACT Rating Scales are assessment tools used to analyze real-life authentic observations of clinicians, parents, and teachers. Prior to developing the scales, a thorough research review for each scale’s focus (i.e., Social Communication, Articulation and Phonology, Language Functioning) was conducted. Next, the most predictive areas in education and social interactions that are affected by poor articulation and phonology, oral expression and spoken language comprehension, and social communication were analyzed. Teachers and parents were asked to complete surveys to provide their input on the potential impact of deficits in these areas. Based on research review, analysis, and input from teachers and parents, a list of questions were developed. A pilot study was then conducted with over 100 students for each of the IMPACT rating scales. Items were reviewed for content quality, clarity and lack of ambiguity, and sensitivity to cultural issues. Once the pilot studies were validated, some questions were eliminated and supplemental questions were added. Then, a final list of questions was prepared and finalized for each rating scale. The scales were then normed in the second phase of the standardization project.

Normative data for the IMPACT Rating Scales was based solely on typically developing children to allow for high sensitivity and specificity. Since the purpose of the IMPACT Rating Scales is to help to identify speech and language disorders and the impact of these disorders, it was critical to exclude students from the normative sample who had diagnoses that are known to influence each area of speech and language (Peña, Spaulding, & Plante, 2006). For example, students who had previously been diagnosed with a specific language impairment or learning disability were not included in the normative sample for the IMPACT Rating Scales. Further, students were excluded from the normative sample if they were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, hearing loss, neurological disorders, or genetic syndromes.

Additionally, research has suggested that we consider the potential impact of biases when evaluating an assessment tool. Responses to questionnaires, tests, and scales, may be biased for a variety of reasons. For example, response bias may occur consciously or unconsciously and when it does occur, the reliability and validity of our measure will be compromised. The IMPACT Rating Scales use balanced set of questions in order to protect against response biases. A balanced scale is a test or questionnaire that includes some items that are positively keyed and some items that are negatively keys.

Here is an example taken from the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale. Items on this scale are rated on a 4-point scale (“never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “typically”). Now, imagine if we asked a teacher to answer the following two items regarding one of their students:

- Appears confident and comfortable when socializing with peers.

- Does not appear overly anxious and fidgety around group of peers.

Both of these items are positively keyed because a positive response indicates a stronger level of social language skills. To minimize the potential effects of acquiescence bias (“yea-saying and nay-saying” when an individual consistently agrees or disagrees [Danner & Rammstedt, 2016]), the test creator may revise one of these items to be negatively keyed. For example:

- Appears confident and comfortable when socializing with peers.

- Appears overly anxious and fidgety around group of peers.

Now, the first item is keyed positively and the second item is keyed negatively. The revised scale, which represents a balanced scale, helps control acquiescence bias by including one item that is positively keyed and one that is negatively keyed.

To read more about the psychometric properties of each IMPACT Rating Scale, please review the technical manual for each scale.

IMPACT Rating Scale Series

Each of the IMPACT Rating Scales is composed of several target areas.

The IMPACT Articulation and Phonology Rating Scale items focus on: speech characteristics, social interactions, academic and home/after school life.

The IMPACT Language Functioning Rating Scale items focus on: spoken language comprehension, oral expression, language processing and integration, literacy, and social language skills.

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale items focus on: social context, intent to socialize, nonverbal language, social interactions, theory of mind, ability to accept change, social language and conversational adaptation, social reasoning, and cognitive flexibility.

IMPACT Rating Scale Case Studies

Case Study One – Evelyn is a 9-year-old, fourth grade student who is currently receiving speech services for articulation. It is her triennial review, and the results of formal and informal assessment have revealed she is 80% accurate in her speech production. The SLP is considering whether or not it may be time for Evelyn’s dismissal from speech services, however, Evelyn’s parents and classroom teacher continue to have concerns that Evelyn is difficult to understand at times and that the speech disorder is impacting her self-esteem. As part of the comprehensive speech and language evaluation, the SLP decides to include the IMPACT Articulation and Phonology Rating Scale to evaluate the potential effects that Evelyn’s speech difficulties may have on her academics and social interactions. Specifically, the rating scale focuses on the following areas: (a) speech characteristics, (b) social interactions, (c) academics, and (d) home/after school life. The speech-language pathologist, Evelyn’s teacher (Mr. Woods), and Evelyn’s mother completed The IMPACT Articulation and Phonology Rating Scale.

The SLP observed Evelyn on three separate occasions in her classroom (twice) and at lunch time with her peers. In the morning, Evelyn appeared confident talking to her friends before the bell rang, but when a student asked Evelyn to repeat herself, her face went red and she said, “never mind” and looked down at her desk. During class time, Evelyn answered a question, which appeared to be understood by the teacher and classmates. The SLP also observed Evelyn at lunch time with her friends. They were talking about the movie they watched over the weekend at a sleepover. Once again, one of Evelyn’s friends made a confused face and asked her to repeat herself. Evelyn appeared upset, crossed her arms, appearing to “shutdown.”

Mr. Woods, Evelyn’s teacher, noted that when Evelyn gets excited or very interested in a topic, and she speaks at a fast rate of speech, her speech errors become more noticeable and impactful to her intelligibility. Mr. Woods also reported when Evelyn increases the length of her responses (e.g., phrases to longer sentences), it becomes more difficult to understand her. Additionally, Mr. Woods believes Evelyn is aware her speech is different from others and that she compares how she speaks to classmates. Evelyn often appears embarrassed and reserved after she is misunderstood or asked to repeat herself.

Evelyn’s mother had similar concerns to Mr. Woods and reported that when Evelyn increases the length of her speech, it becomes more difficulty to understand her. Evelyn is aware that her speech is different than her friends and her siblings, and has asked her parents why she doesn’t speak “normal.” Evelyn’s mother is concerned about Evelyn’s confidence and how her speech impacts her self-esteem.

The SLP gathered the IMPACT Articulation and Phonology Rating Scale data from Mr. Wood’s and Evelyn’s mother and inputted her own rating scale observations on the Video Assessment Tools website. The IMPACT calculator indicated that there indeed was a significant impact, meaning that Evelyn’s speech impairment is indicative of/significant enough to affect everyday communication, academic performance, and social interactions.

The SLP is reviewing the formal assessments that indicate Evelyn’s articulation as 80% accurate and is now considering the overall impact of the speech sound disorder. Based on both formal and informal assessments, the SLP has determined that Evelyn continues to qualify and benefit from speech services. Although Evelyn’s overall speech intelligibility has improved, she still presents with a mild speech sound disorder that is impacting her both academically and socially. Evelyn will continue to receive speech services and new goals will be implemented that target Evelyn’s rate of speech, confidence, and social interactions.

Case Study Two – Dereck is a 16-year-old, tenth grade student who a diagnosis of specific learning disability and speech-language impairment. He is placed in a mild-moderate classroom. His parent wants him to continue with speech and language services, however, his file review reveals he has made minimal progress over the past few years. Dereck was last assessed for speech and language when he was in the seventh grade, and his triennial assessment is due next month. The SLP who is assessing him has worked with him over the past year (ninth grade) and is reviewing her notes and progress reports. The SLP begins compiling the tools she will use for assessment. She includes the IMPACT Language Functioning Rating Scale. Specifically, the rating scale focuses on (a) spoken language comprehension, (b) oral expression, (c) language processing and integration, (d) literacy, and (e) social language skills. The speech-language pathologist, Dereck’s teacher (Ms. Vandenbraak), and Dereck’s father completed The IMPACT Language Functioning Rating Scale.

The SLP observed Dereck in his classroom (two times) and at lunch time. During the first classroom observation, Dereck was working with two of his peers on an English project. The class had just finished a short story and were discussing the theme and key details of the story. Dereck was observed participating, but his comments were off and he didn’t appear to understand what his peers were saying about the story. The SLP observed Dereck as he appeared to get frustrated at the project. He didn’t understand what the story was about or why they needed to do the project. He was angry and walked over to the side of the room to sharpen his pencil. Dereck currently has a speech and language goal in spoken language comprehension, and this was similar experience what the SLP often saw in their speech sessions. Dereck has difficulty with comprehension of spoken material. The SLP often shortens the amount of information that Dereck receives at once, and then reviews, and then continues. This appears to sometimes help Dereck with his understanding and building connections. When Dereck gets frustrated or upset, the SLP and him work on strategies to calm himself. The SLP’s next observation was during a five minute break in Dereck’s math class followed by instruction. Dereck was observed sitting with three other students. The students were talking about their weekend and Dereck was able to make appropriate comments to the conversation. When class started back up, the teacher began her lesson followed by word problems on the board. Dereck appeared very confused. He was looking around at his classmates but did not ask for help.

Ms. Vandenbraak, Dereck’s English teacher, reports that he can be an engaged student but has difficulty following along with the material. His reading skills are appropriate, however, he struggles with vocabulary and his listening comprehension. He has difficulty answering basic WH questions, understanding grade level vocabulary, following along with teacher instruction and classroom discussions. As per the accommodations in Dereck’s IEP, the teacher makes sure to always provide Dereck with a copy of notes and assignments. The teacher noted that Dereck benefits from spoken language being repeated and/or simplified. He understands and attends to what is going on around him and demonstrates an understanding about events that have happened in the past. When recalling a story or an event, Dereck has difficulty with maintaining the sequence. Additionally, he appears to have difficulty asking and answering questions in class.

Dereck’s father also completed the parent rating form from the IMPACT Language Functioning Rating Scale. His father agreed that Dereck benefits from reduced amounts of verbal instruction at once. Dereck’s father also has Dereck repeat instructions back to him so he knows Dereck understands what is being asked of him. His father indicated Dereck has difficulty following along with family conversations at the dinner table, or when watching television shows. He reported that Dereck is friends with a group of children in his neighborhood. They often play outside riding their bikes, scooters, and playing tag. There have been occasions where Dereck comes in from playing appearing upset and left confused by conversations. Overall, his dad does not believe his communication is impacting his friendships at this time but he is concerned for the future.

The SLP gathered the IMPACT Language Functioning Rating Scale data from Ms. Vandenbraak and Dereck’s father and inputted her own rating scale observations on the Video Assessment Tools website. The IMPACT calculator indicated that there indeed was a significant impact, meaning that Dereck’s language impairment is indicative of/significant enough to affect everyday communication, academic performance, and social interactions.

The SLP is reviewing the formal assessments that indicate Dereck’s language functioning is below average when compared to his peers. The SLP is also reviewing progress reports from speech and language sessions and has found he has made minimal progress over the last year. Lastly, the SLP looks at the results of the IMPACT Language Functioning Rating Scale and can see that there is a significant impact of Dereck’s language skills on his everyday communication, and academic success. Even though Dereck’s progress is limited, the impact of the disorder continues to qualify Dereck for speech and language services. Dereck will continue to receive speech and language services and new goals will be implemented that target Dereck’s understanding of spoken language in academic and social contexts.